I need help. Problems in philosophy are as old as time, and what I'm doing I'm sure is just putting my own personal spin on a conundrum that many, many people have encountered. Nevertheless, I'd love some guidance about how to approach the issue.

I lived in Korea for seven years on Yongsan Garrison, an American military base in the middle of the capital city, Seoul. I graduated from both Seoul American Middle School and Seoul American High School, living, studying, and growing up between the sluggish base and the bright Korean metropolis.

Prior to moving to Seoul, we moved from place to place, spending no longer than 2-3 years in each location. Once we left, we never returned. All I have left of each location I grew up are the memories of those places (and of course, the corroborating accounts of the people in my family who moved with me).

Once I graduated high school, I left Seoul to go to college in New York. As of today, I have spent about three years away from the place where I spent my formative years. With one exception (a one-week reunion with my best friend from high school) I have not had any direct contact with anyone I knew in Korea who isn’t my direct family. The only remnants I’ve seen of my life in Korea are the occasional social media updates that old teachers and students post.

You might be getting some idea about where this story is going. It’s going to take a dramatic turn. The US Military has recently declared that Yongsan Garrison will close in 2019. The place where I did the most growing up is going to be wiped off the face of the map and replaced with a park. Politically speaking, this move was a long time coming. Americans really don’t need to be occupying the most valuable real estate in Korea with a bunch of ugly, outdated military buildings from the 50s.

This is pretty nostalgia-worthy on its own, but more importantly, it got me thinking about the criteria we use to verify our own memories. Let’s say that I have coffee with my friend Matt at Coffee Shop X at time T. A day later, I want to verify that the thing that I remember, this memory I have of drinking coffee with Matt, actually occurred. An obvious thing to do would be to find Matt and see if he has the same memory, and if it accords with mine, then conclude that this is enough evidence for my memory to have happened.

But if the issue at hand is that I want to have some criteria of verifying my own (human) memory, then it doesn’t really make any sense to use someone else’s own (human) memories as evidence for the veracity of mine. The thing that bothers me about this solution is that I’m looking for an independent criterion to verify my own memory, one that doesn’t depend on the memories of others.

So the next obvious thing for me to do is to return to Coffee Shop X. By doing this, I can examine the way the coffee shop looks and smells, its location, the hardness of the tables, even the taste of the coffee I ordered, and if this sensory evidence accords with my memory of coffee yesterday with Matt, then it seems that I have some way of independently establishing some kind of evidence for the veracity of my memories.

It seems to me that at least superficially, something important is to be gained by going back to the location that we remember memories taking place. Which is where my own conundrum comes in:

Going back to the location of my memories of my middle and high schools is unavailable to me. All physical evidence of the base will be gone (well, not entirely: as I understand a museum of the history of the base will be built in the park, but for the purposes of this discussion that doesn’t seem too relevant). If going back to the location of a memory is a good way to independently verify memories, then how can I verify the memories I have of living on base and going to school there for seven years?

To make this more concrete, I want to give a toy example. Let’s say in high school, I hid a pencil somewhere in my school (perhaps in a secret compartment in one of the walls) and didn’t tell anyone about it. Nobody but me knows, and there is not the slightest chance that anyone but me will find the pencil. Once the school is gone, the physical evidence of my hiding the pencil is also gone. The surest way for me to independently find evidence for the truth of my memory (i.e., finding the pencil) is also gone. Is the memory of my hiding the pencil any less legitimate than my memory of making my bed in the morning, which can be easily verified by walking into my room and seeing my bed made?

Whether going back to the location of a memory and examining the physical evidence to verify a memory is enough evidence to judge the veracity of a memory is a good question. In discussions with friends and professors, it seems like a common line of reasoning is that all human experiences that are not occurring at this very moment are memories. Since everything is in flux, and no memory’s setting is exactly the same when we revisit it, no memories can be trusted and so my dramatic case is no different from the ordinary case. Not being able to confirm our memories is just a fact we have to deal with.

But this objection doesn’t negate the central worry: it only provides a degree of graduation. Surely, when we recognize the setting of a memory, it means something. Even if we can’t accept the idea that we can completely verify a memory’s veracity, if the feeling of recognition exists, then being able to go back to the setting of a memory and gaining that bit of evidence provides more certainty than otherwise. So are my memories less legitimate than the memories of someone who can go back to their old school and find the pencil that they hid there?

So, to sum it up, here are the questions I have: what, if any, are good ways to independently verify that memories have occurred? If revisiting the setting of a memory is a good way to do this, then does it follow that my memories of high school are less legitimate than the average high school memory (because I have less of a setting to go back to than others)? Is there then a way for me to “reclaim” my memories? Is there something I’ve missed or haven’t considered thoroughly yet?

I’d love to hear your point of view or perhaps some written sources about this conundrum. It’s difficult to sift through the wealth of epistemological work without some guidance (and I’m sure this problem has been discussed at length many times). Thanks in advance!

Lonely Nut Club 2.0

My thoughts, musings and essays. Occasionally a travel blog. Occasionally published elsewhere.

Monday, January 28, 2019

Monday, January 21, 2019

The Right Way to Eat Korean Barbecue

Or: Life Lessons from a Bunch of Tasty Meat

Korean barbecue is a phenomenon that has thankfully become a phenomenon in the States, which is fortunate because I was not about to give up my grilled meat when I came back the States. During the seven years I lived in Seoul, Korean barbecue happened at least once every two months or so (whenever my Korean grandfather came to visit, for instance, which was often).

Oh, the gluttonous joy that came from these meals. Koreans are experts at stuffing themselves, and a typical KBBQ experience entailed stuffing myself with enough meat, rice, and side dishes to explode… and then finishing the evening with one or two more gut-busting noodle and soup courses before sprawling on the floor and stacking the mats as pillows to snooze off the calories (the only reason this was okay was because I was pretty young- not recommended for general audiences). We did this often, and we went hard. It’s a total Korean experience, the full package.

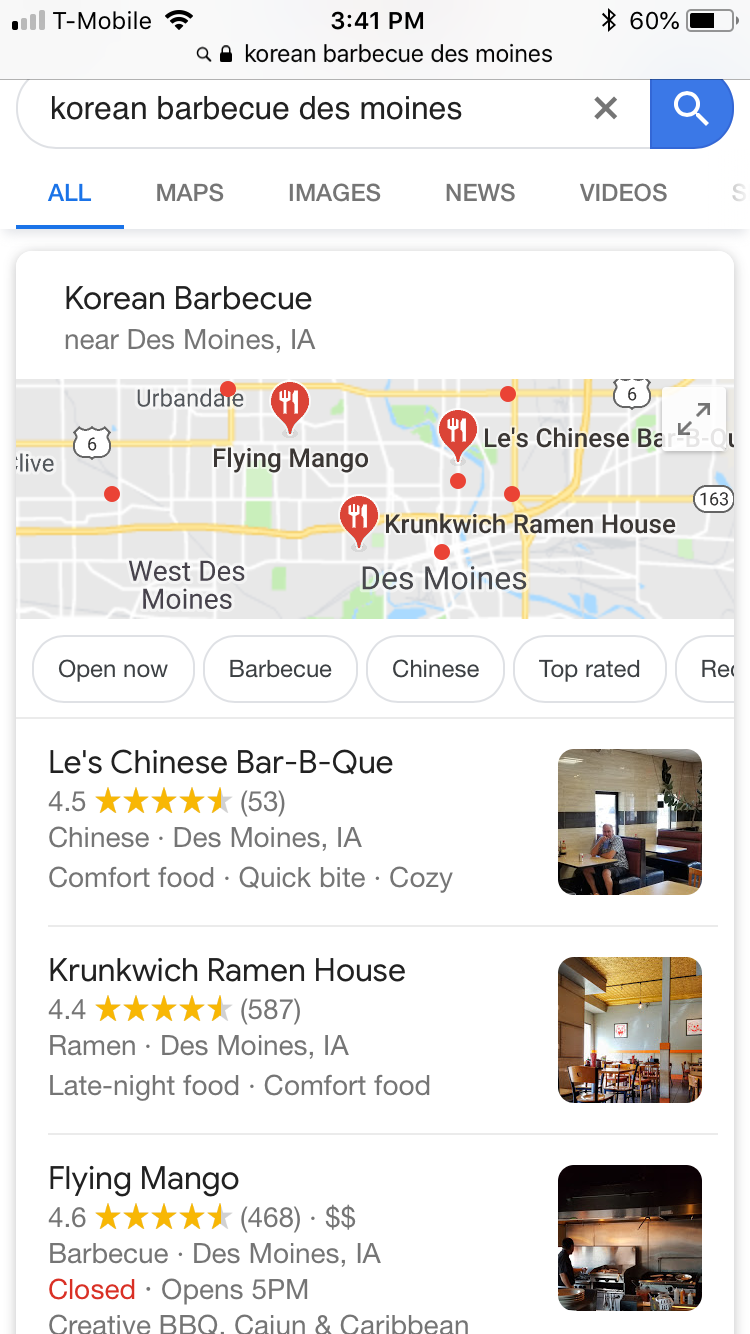

Anyway, I was talking to a poor soul from rural Iowa and who insisted that there is no such thing as Korean barbecue there. Skeptic that I am, I googled Korean barbecue places in Des Moines, and unfortunately, this is what came up:

I kind of wanted to laugh when I saw that the top result was “Le’s Chinese Bar-B-Que” but instead I kind of died a little on the inside instead. Iowans, this is a significant market opportunity! Bring KBBQ to Iowa!

So this conversation led me to believe that there exists a non-trivial cohort of Americans who have never had the true KBBQ experience. There are a number of “guides” for eating Korean barbecue online, but for the most part these are just descriptions of what’s going to come out, with very few if any practical guides for how to enjoy the food the most. Far and away the best thing I found at KimchiTiger (which by the way is an awesome blog with content I can really get behind) here: https://kimchitiger.com/blogs/all/18063299-how-to-eat-korean-bbq-like-a-korean.

The article is great, but there are a few finer points I think it misses. First of all, most KBBQ tips advise getting samgyupsal (pork belly) or kalbi (marinated short rib), both of which are delicious and worth trying. But it’s also worth noting that samgyupsal tends to be one of the cheapest options, while kalbi is going to be one of the more expensive things on the menu.

Also, nobody seems to talk enough about dyejigalbi (marinated pork ribs) enough! When we lived in Korea, it was the only thing we ordered when we went out for barbecue. It’s all the tender deliciousness of marinated meat that you get with beef, minus some of the expense. Also sometimes I’m just not feeling the greasy pork belly feeling.

The other thing I love about the KimchiTiger article is it actually shows you how to use ssam to make your little lettuce package of joy, which is something so Korean that all your Korean friends will be shocked if you do it out of the box (assuming you’re not Korean, of course).

But the personal beef (heh) that I’m going to bring up is that the major mistake people make when they eat Korean barbecue is to assume there’s a right way to eat Korean barbecue. Aha, the clever ruse of the title has been exposed!

I don’t know, maybe when you’re eating a filet mignon it’s not really proper to chop it into little pieces and mix it with the salad or something. But the best way to approach Korean barbecue—and Korean food in general—is to take advantage of the extraordinary wealth of options that come in the form of all these delicious side dishes and accompaniments and really experiment to find something delicious.

Try eating a piece of meat with just the marinated onions. Then try doing that plus a piece of kimchi, or maybe a spoonful of buckwheat noodles (nengmyun). Or maybe you’ll dip it in ssam-jang and sample with a sesame leaf, or eat it with a piece of tofu, or maybe you’ll put five different side dishes and three pieces of meat on a lettuce leaf (which you must eat whole—no bites).

My point is, there are really no wrong answers. Probably the worst thing you could do while eating Korean barbecue is to assume there is a right answer and deprive yourself of the opportunity of mixing and matching so many different flavors and textures. (who knew such a delicious medium could be a metaphor for life?)

And if at the end of the day the mixing and matching doesn’t do it for you, then by all means feel free to revert back to dipping the meat in salt/oil and eating it with rice (just know that people like me who live for flavor combinations will definitely judge you for this).

Just don’t do anything too weird, like eating your chopsticks, and if you find a flavor combination that is delicious then I’m sure your table companions will applaud you.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)